Floyd Bralliar, Knowing insects through stories, New-York, Funk & Wagnalls Company, (1918) 1921, pp. 202-207.

Stones that move.

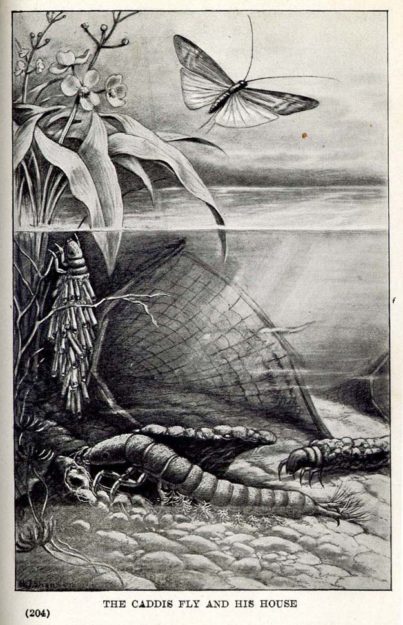

Some day when you are lying on a sand-bar with your head out over the water, watching minnows playing among stones, hoping to catch a snail who has been so unwise as to creep out of its shell far enough to have its head bitten off; or watching a stone-fly who has fooloshly erept from under its stone, expeeting to get a good dinner and get back again without being seen, you may be surprized to see a bunch of pebbles and shells crawling about on the bottom. You have always been tanght that stones can not move, and you will perhaps wonder if you are not dreaming, or if the running water has not addled your brain just a bit. If you will watch just a little more closely, you may see this bunch of pebbles move over a worm, or a tiny snail, and after it passes on, the worm or the snail will be there no more.

You may pick up this cluster of pebbles and see nothing but a few pebbles that have in some way stuck together, and may think they are just a piece of pudding-stone. There is not hole nor door, so nothing can be Inside, and there certainly are no legs, so how could it move? If you drop it back into the water, after a while it will begin to move. A tiny minnow may let his curiosity get the better of him and begin swimming about this pudding-stone to see why it is moving, when something happens and the foolish minnow disappears Inside the cluster of stones. He learns why it moves, but he never comes back to explain the matter. If you will get this pudding-stone again and look very carefully, you will find there are tiny crevices between these stones. If you wil take your kniffe, you can pry them apart, and the secret of the moving stones is out. These stones were tied together with silken cords, glued fast to the stones instead of being tied around them. There is a silken room on the inside and the wise builder of this home merely fastened these stones to it to make it invisible. Some of these creatures even fasten a live snail to their house of stones, as a foil, and thus more easily delude and trap their unsuspecting victims. Had you shaded your eyes and looked carefully at this movinh stone, you could have seen a head and the front parts of a fat white larva sticking out of the front of the house. He was dragging it with his front legs. This was why the stoned moved. The body being white, it merely looked as tho the light sparkled in the dancing water.

If you will be more careful in your observation, you will find a silken net stretched among the pebbles somewhere near the moving stone house. This net open up stream so that it can catch any creature that may be coming that way down stream. Little minnows usually swim near the bottom when not feeding, and slip between stones that line the bottom. As these nets stretchs from one stone to another, the fish is in the net before it knows it. These nets are made and set by these little stone dwellers much as a speder weaves her web. Perhaps she is the skilful Fisher that taught human fishers how to construct their first nets. I think you will realize, when you investigate it thoroughly, that most of the inventions men have made appeared first as the outworking of the wisdom God gave to some one or other of our little neighbors.

All these little creatures do not build houses in this way. Some build in the form of a chimney with a door at the top. Others collect dead leaves that fall into the water and construct a home that looks like part of the background of the sunken leaves at the bottom. In regions where moss and algae are plentiful in the bottom of streams or ponds (for some of these creatures live in still water) you will find varieties living in houses constructed of moss, the interior, of course, always lined with silk. Many of these creatures do not fish at all, but feed on plants of various kinds. It is wonderful how many creatures live under the water. I have sometimes wished I could live under water for a time and become really acquainted with the wonderful world that lies under the surface. Aftert hese fat, white gribs are fully grown, they add stones, leaves, or moss, as the case may be, to their house to make it more secure. They shut the door as tightly as any other part of the house and then change into a pupa and go to sleeep…/… To me the caddis fly has always taught this great lesson: « In whatever state we are, let us therewith be content » This soft, helpless little worm finds itself on the dark bottom of a stream, exposed to danger of every sort. Instead of giving up in hopeless despair, it sets about and builds a veritable fairy-land of its own. Out of its own poverty it builds a palace that has attracted the wonder of the world’s greatest and most learned men. A great variety of structures is build by these caddis worms, but there is only one family, and there are comparatively few varieties in this family. Yet they are widely scattered over this land of ours. In fact one can scarcely find a stream running the year around that is not populated by some sort of caddis fly.