Henry Scherren, Popular Natural History of the Lower Animals.(Invertebrates), Londres, The Religious Tract Society, (1903), 1908, pp. 124-126.

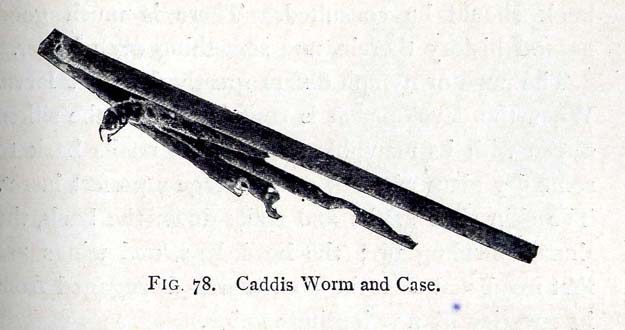

It is in the larvae, and the cases which they construct, that the chief interest of theses insects lies for the naturalist, and the angler knows them to be excellent bait. Two or three days after the larva has emerged from the egg it sets to work to make a sheath, which is of different materials, according to the species-pieces of grass, leaves of duckweed, short lengths of rushes, longer pieces of reed, grains of sand, small stones, and shells, often with the rightful owners still occupying them. The case represented in Fig. 78 was taken in a backwater of the river Gipiong, not far from Ipswich. The piece of reed attached to the case on the right side measures just three inches ; and this appendage is the longest I have ever seen. The material of the sheath are held together by silken threads spun by the larva, and the sheath itself has a silken lining…/…

Readers of Water Babies will remember how Tom met with a Caddis at the end of its larval stage, and « broke to pieces the door, which was the prettiest little grating of silk, stuck all over with shining bits of crystal ; and when he looked in the caddis poked out her head, and it had turned into just the shape od a bird’s »…/…

It is very easy to collect a number of these larvae which need no care in an a aquarium beyond being supplied with plenty of growing weed for food. If a case be carefully picked to pieces the larva will make another, and beads and fragments of mica supplied for the purpose have been utilized. Strange guests are often found in theses cases. I have notes of rotifers of two species, a mote, some small crustaceans, Young water wood-lice, and worms all living inside one case.