William Hamilton Gibson, Sharp Eyes: A Rambler’s Calendar od Fifty-two Weeks Among Insects, Birds and Flowers, New York, Harper & Brothers, 1898, pp. 299-304.

HOUSE-CARRIES UNDER WATER

February 23d

Last week we made the acquaintance of those queer house-carriers of the trees, the bag-worms, with their thatched and ornamented cocoons now firmly swung among the winter twigs. But there is another house-builder that few of us ever see in its home- the caddis. He lives on the pebbly bottom of the stream or the shallows of the pond. Even as we stood upon the black ice that the edge of the dam, gathering our bag-worms last week, we need only have lain down upon the ice and looked beneath to have seen our caddis crawling upon the bottom, leisurely lugging its stone cottage or log-cabin around him. But who would ever think of going “bug-hunting” in winter? This stream. Locked fast and muffled in ice, or bubbling beneath the snow-drift, its overhanging icy border fringe crowding close upon the ripples in the intense cold, would hardly invite the entomologist as a likely field for specimens. The city naturalist who happens to keep an aquarium knows with what difficulty he can keep it stocked in the winter months if he would depend alone upon the dealers in aquarium supplies. A few lizards, polliwogs, and goldfish are almost their only stock in trade at this season, with perhaps a fine show of green moss in bunches, picked in the woods, which “looks pretty” under water.

“But I want some plants, snails, water-beetles, and crawfish,” I said to such a dealer recently. “Oh, you can’t get anything of that kind now, you know,” he replied. “They’re all dead or froze up. We’ll have plenty of ‘em in the spring.”

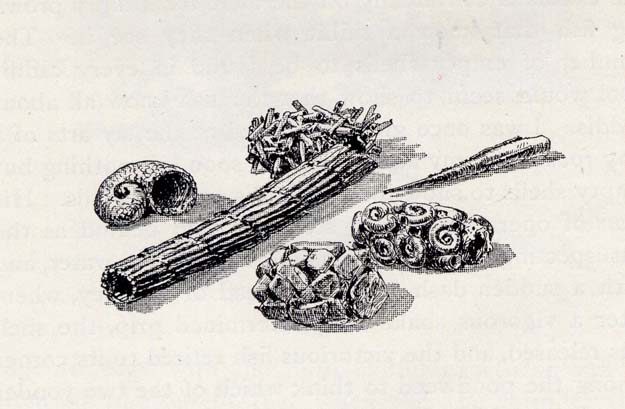

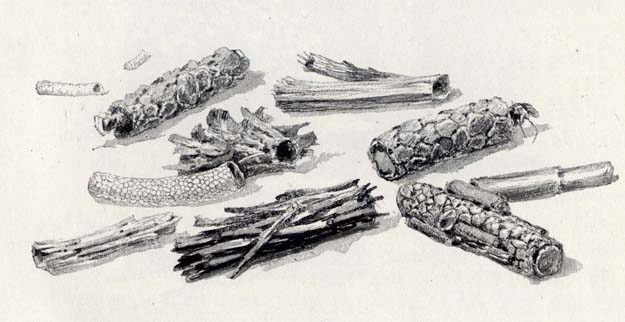

Nevertheless, the film of ice over the pond or stream need be no barrier to the winter naturalist. The mud at the borders of the bank holds a lively harvest, and does not seem to care a snap for the seasons. One good scoop with a strong net will sometimes bring up a veritable summer haul of specimens- fish, frogs, water-beetles, lizards, water-boatmen, dragon larvae, and occasionally a dainty case of the caddis, resembling one of the group which I have here picked yonder pool and laid upon the snow. I have a number of these cases before me as I write, and they are really beautiful works of insect art. As a rule, each species of caddis is true to some particular whim in building or in the choice of materials for its domicile. Here are two individuals that seem to have taken a hint from the bag-worm, and think there is nothing to compare with sticks and leaves. Their cases are about an inch and a half long. Another has carefully selected tubular pieces of floating grass stems or straws, enlarging the tube as its growth requires by slitting up the side and fitting in

(Illustration p. 301)

a strip of new material; afterwards, perhaps, decorating the exterior with a few stray chips or pebbles.

But the most interesting of all are the dwellings of the stone-builders, actual mosaic tubes of carefully-selected pebbles, all joined edge to edge, and neatly closed at the rear opening by a nicely-fitted pebble of larger size. And one there is, the glassy abode of the smaller caddis, a perfect marvel of mosaic art. A small, slightly curved tube about three-quarters of an inch in length (shown directly above the stick case in the illustration), the crystal palace of the most exquisite and gifted artist among all the caddis fraternity. The tube is composed of minute, glassy, flat pebbles, joined edge to edge with the most skilful exactness, and is often so transparent that when wet the form of the dweller may be seen through its wall. Here may the human worker in stained glass find his matchless model. An artist, too, that accomplishes his task without resort to metal frame or solder, the edges of his glass being joined by some insoluble cement of which he hold s the secret.

The art of the bag-worm appears almost commonplace by the side of this rare product. With its ready reserve of silk it is an easy matter for the bag-worm to weave a mere pouch, while the further attachment of the sticks and leaves is mere pastime; but what shall we say of the intelligence that gleans among the pebbles beneath the water, constructing a mosaic tube about its body, even in the current of the stream? This is what the caddis larva does. As in the bag-worm, this case of the caddis serves as a protection against its enemies; and while the basket-carriers in the trees are keeping an eye out for the birds, dodging into their case and literally “ pulling the hole in after them, “ or drawing it close against a twig, on the approach of the enemy, the caddis is continually on the alert for hungry prowling fish that know a titbit when they see it. The number of empty shells to be found in every caddis pool would seem to show that the fish know all about caddis. I was once greatly amused in the sly arts of tiny rockfish in my aquarium that soon left nothing but empty shells to show for my caddis and my snails. His plan of operation was to steal up from behind as the unsuspecting victim was regaling itself in the water, and with a sudden dash grasp the head of his prey, when, after a vigorous shake and determined grip, the shell was released, and the victorious fish retired to its corner among the pondweed to think which of the two yonder- snail or caddis- it would rather have for supper.

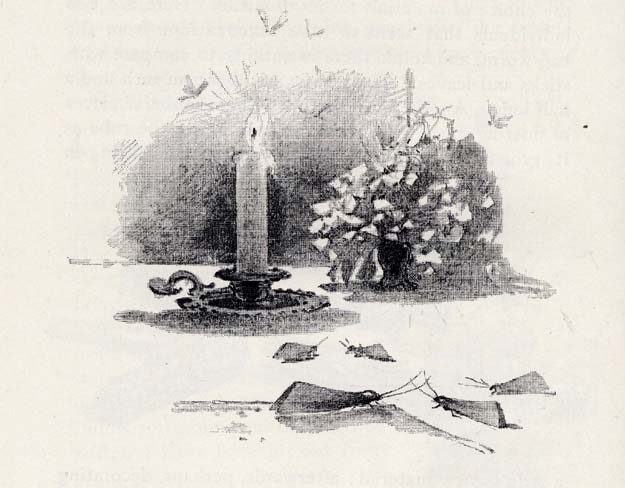

I have said that few of us ever see the caddis in its home. And yet he is an old acquaintance with most of us. There are few summer evenings when he does not make himself perfectly at home around our “ evening lamp” in the country, that brown, circling, moth-like insect, with steep-sloping wings, and such a powerfully strong odor, being in truth the perfected product of these tube-cases beneath the water.

A collection of caddis cases makes a very interesting exhibit. I have shown a group of six foreign species, but it is possible that any one of them may yet reward our search in our native pools. I have found three specimens that closely resemble some of them.