Christopher Reynolds, The pond on my window-still, The story of a freshwater aquarium Londres, Andre Deutsch, 1969, pp. 85-94.

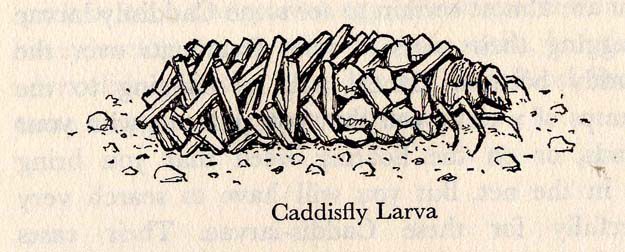

If you look down into the water of the pond you visit you are almost certain to se some Caddisfly larvae dragging their cases of stem fragments over the muddy bottom. Others will be clinging to the clumps of water weed that you pull out with your hands or on the floating weed that you bring up in the net. But you will have to search very carefully for these Caddis-larvae. Their cases of plant material not only protect the soft bodies of the larvae, but serve as a wonderful camouflage.

There are many kinds of Caddis-larvae. Each kind chooses a particular material for building its case, and arranges it in a special pattern. Thus you can usually tell the kind of Caddis-larva by looking at its case alone.

Most of the Caddis-larvae that I dredge from the bottom of the pond have cases made from bits of plant stem placed crosswise on the case. This gives them a very spiky appearance. Others have cases made entirely from small snail shells. The kinds that I find on the water plant near the surface have more slender cases, made from pieces of leaf and stem place lengthwise.

However, if the materials that the caddis-larvae naturally choose are not présent, they build cases from what is at hand, if given enough variety. For example, there are very few bits of stem on the floor of my aquarium, and so the Caddis-larvae that had built from loose stem fragments now began to fix small gravel stones to their cases. As they always build forwards these larvae soon had the front half of their cases patterned with little stones of different shapes and colours. This made an interesting contrast with the criss-crossing stems that now formed only the hind part of their cases.

The caddis-larvae with cases of small shells used the snail shells in my aquarium. They did not mind whether the shells they used contained living snails or not. Thus some of my little snails ended their lives cemented together,, like bricks on a round chimney.

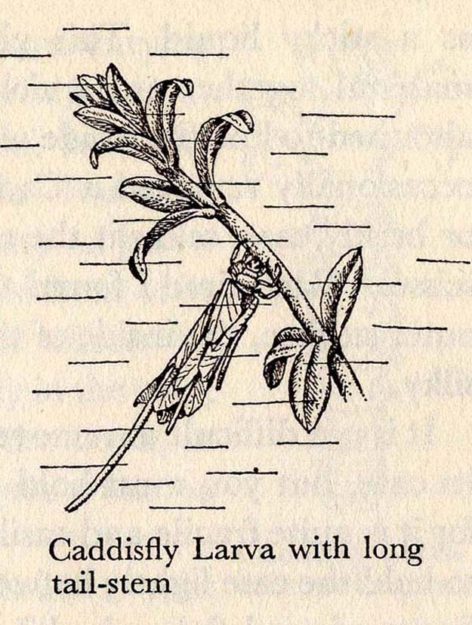

Other Caddis-larva, seeking material for enlarging their cases, used their jaws to cut out pieces of leaf and stem from plants growing in my aquarium. Some of the larvae always cut one or two pieces of stem about twice the length of their cases, and fixed these so that they extended backwards, like long, stiff tails. These tail pieces often hampered the larvae by getting caught up in the plants of the aquarium. However, in a pond they would probably give an added protection to a Caddis-larva by making its case more difficult for a Moorhen or a hungry fish to swallow.

You only see the front part of a Caddis-larva extending from its case as it moves about in the aquarium. This look very like the front part of a caterpillar. But whereas the caterpillar’s thre pairs of legs behind its head are short, the Caddis-larva’s second and third pair are fairly long. These second and third pairs are used for crawling or climbing plant stems. The short first pair, however, is used for holding particles of building matter, which the larva fixes with silk from its mouth to the front edge of its case.

The silk comes out of the Caddis-larva’s mouth as a sticky liquid. This glues the piece of case material together and quickly hardens. The silk is also used to line the Inside of the larva’s case. I have occasionally removed a Caddis-larva from a rough or bristly case, and slit the case open with a pair of scissors. Each time I found that, in contrast with its outer surface, the Inside of the case was smooth and silky.

The silk comes out of the Caddis-larva’s mouth as a sticky liquid. This glues the piece of case material together and quickly hardens. The silk is also used to line the Inside of the larva’s case. I have occasionally removed a Caddis-larva from a rough or bristly case, and slit the case open with a pair of scissors. Each time I found that, in contrast with its outer surface, the Inside of the case was smooth and silky.

It is not difficult to remove a Caddisfly larva from its case, but you must hold the case very carefully, for it is quite fragile and easily crushed. What I do is to hold the case lightly between the thum and forefinger of my left hand while I push a narrow stem gently into the hole at the back of the case. The larva does not like to have the sensitive rear portion of its body touched, so it crawls out from the front of the case with its rear end tucked underneath-like a nervous dog creeping away with its tail between its legs. I then drop the naked larva into a saucer of water, so that I can examine it.

Without its case, the Caddis-larva looks a very defenceless creatures . Its head and the front part of its body, which bears the legs, are Brown, with a horny skin. The hind-body, normally kept within the case, is soft and yellowish-white. When I look at the hind body Under a pocket lens, I can see two rows of thread like filaments along its sides and bending over the back. These are the gills, for the Caddis-larva breathes under water. The hind body ends in two sharp, forward curving hooks. These grip the silk lining at the base of its case and hold the Caddis-larva firmly in. For this reason you must never try to pull a Caddis-larva out from the front of its case. It will resist your efforts by hooking itself more firmly in the case; and you would injure the larva, or even tear it apart, if you went on pulling.

As the naked Caddis-larva rests on the bottom of the saucer, it waves its hind body up and down with a steady rhythm. This waving motion of the hind body continues when the Caddis-larva is in its case. At the beginning of the larva’s hind body there are three fleshy lumps one on top and one at each side. The lumps hold the larva centrally in the case, leaving rom for water to pass between them. A current of water, caused by the rhythmic movement of the larva’s hind body, enters the front of the case and leaves through the hole at the back. In this way the larva keeps its gills supplied with fresh water while remaining in its case. Sometimes a Caddis-larva with a case of thin leaves shows up against the bright daylight, as it clings to a stem near the surface of my aquarium. Then I can just see the shadowy movements of its hind body through the pale green of its case. On one occasion after removing a Caddis-larva from its case. I Put the empty case in the saucer with the larva. Then I waited to see what the larva would do. It crawled round the saucer until it reached the empty case. As soon as it touched the case it became interested, and clambered all round and over it, from one end to the other and back. After about two minutes of carefully examining the case by prodding it with its mouth an front legs, the larva finaly moved in. It entered through the hole at the back of the case, and a fews seconds later poked its head out at the front. It twisted its head over and round the opening to examine the front of the case with its mouth and forelegs. Then, satisfied that all was well it hooked itself firmly in and started to crawl round the saucer. I picked it up and restore dit to the aquarium.

I removed another Caddis-larva from its case and droppe dit into the saucer. Then I gave it back its own case to see if it would behave in the same way. This second larva was much more cautious, and examine dits case for fifteen minutes before moving in. It entered the case at the front opening and pushed its head out through the narrower hole at the rear. Now the caddis-larva started to crawl across the saucer with its case on back to front. I put it back in the aquarium.

I thought it would be rather fun to see if the Caddis-larvae would build themselves cases of really Bright material, so thatI could use them to decorate the aquarium. I collected pieces of gold and silver paper and the coloured metallic papers from chocolate creams. When I had a good selection of these I cut them into small fragments and scattered them in a saucer of water. I then removed two caddis-larvae from their cases and put them among the glittering fragments. The Caddis-larvae wandered around the saucer, looking for something to cover their nakedness. Now and again one of the larvae would pick up a fragment, turn it over and examine it, then drop it and move on. They did not seem to like the feel of the metal paper. However, after half an hour, one of the larvae had fixed a few pieces very loosely round the front of its body. I waited another half hour, but it made no attempt to dress itself further, or even to handle any more fragments. The other larva was still naked.

As this silver paper experiment was not a success, I cut up bits of coloured paper from magazines, and placed these in another saucer of water. Then I put the two Caddis-larvae among them. They immediately showed an interest in the softer paper and started picking up pieces and feeling them with their mouths. An hour later they had both made little collars of coloured paper and were fixing more bits in front of these. I notion that the Caddis-larvae did not select any particular colours. Their paper collars were made from a fair sample of the different colours in the saucer.

It was now time for me to go to bed, so I moved the larvae and the coloured fragments into a small dish with more water, and left were loosely dressed in paper fragments. With little coloured streamers waving around them as they crawled about, they looked as if they were about to take part in some underwater carnival.

I now put the two Caddis-larvae back in the aquarium. Here they started to pick up bits of gravel from the aquarium floor, and had soon built circles of little stones in front of their paper dresses. In a couple of days each larva had a new gravel case with two or three coloured strips of paper at the back.

I did not throw away the metallic paper fragments that had been scorned by the two larvae. Instead, I scattered them on the floor of the aquarium to see if any other larvae would make use of them. To my surprise, a week later several of the Caddis-larvae had glittering patches of metallic colour on their cases. Encouraged by this, I cut up more wrapping from chocalate creams- the gayest I could find- and dropped the pieces into the aquarium. The Caddis-larvae were quite willing to mix these among the stems, leaves, and gravel stones they used for building. It was not long before many of them sparkled with points of silver, gold, red, violet, green, and blue, as they crawled over the gravel, clambered up the stones, or climbed the stems in my aquarium.

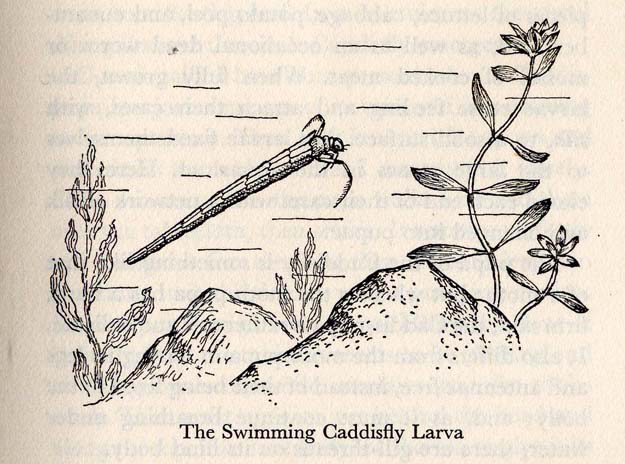

I have not yet mentionned the swimming Caddis-larva. This is a very dainty creatures with a long, slender case, tapering almost to a point at the back. The case is made entirely from small pieces of leaf, all cut in near ellipses and carefully arranged in rows that spiral forwards. The swimming Caddis-larva feeds on the leaves of water plants, and as it swims from one clump to another, it looks like a piece of green stem prpelling itself through the water. The larva uses its long, feather hind pair of legs to swim with. These swimming legs curbe right over the larva’s head when it is resting on a leaf or stem. I particularly like to watch this charming little Caddis-larva as it glides to and fro, like an animated stem, through the mid-water of my aquarium.

Most Caddis-larvae feed on the same kind of varied materials as Water-Snails. Like caterpillars, they have strong jaws, and they nibble their way through the leaves of water plants. They also like pieces of lettuce, cabbage, potato-peel, and cucumber rind, as well as an occasional dead worm or morsel of cooked méat. When fully frown, the larvae cease feeding and attach their cases with silk, to a solid surface. My larvae fixed themselves to the large stones in the aquarium. Here they closed each end of their cases with a network of silk and changed into pupae.