Clotilde von Wyss, Living creatures : Studies of Animals and Plant Life, Londres, A. & C. Black, 1927, pp. 59-67.

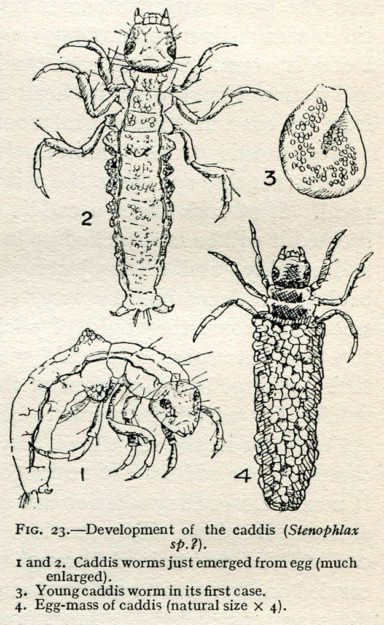

The caddis worm, in flowing water, are more easily seen, If we settle down on the bank of a canal or sluggish stream, and Watch the ripples stir the grass roots, and whirl Dead leaves and other debris in a slow dance from stone to stone, our attention may be arrested by small bits of stick, cither resisting the force of the water or movung at an angle to the direction of its flow. We secure a few of the small, apparently inanimate objects that seem to defy Newton’s laws of motion. The discovery will at once be made that the pieces of stick or roots, as well a small particles of mud or stonc, are held together in tubular form, and that the tube itself is inhabited. The owner soon appears at the wider opening of the case, presenting several legs and a dark coloured head. Even more of the body may presently be revealed especially if we place the animal in some water in the hollow of our hand. It will then be seen that behind the dark head is a segmented almost worm-like body, soft and weak, and covered with thick soft threads. There are three pairs of strong legs dispkaying the structure typical insects. More than this the creature does not vouchsafe to display and as we firmily but gently take hold of the front of the animal and try to remove it from its case, it becomes quite obvious that it is attached to the case in some manner, and that our purpose cannot be fulfilled without inflicting grievous bodily harm. This is a typical caddis worm. However great may be the variety these insects display in the mode of constructing the case, in the locality in which they drive, and even in personal appearance, their general manner of living is the same. They are obviously not worms in the scientific sense of the word; their well-developed head with strong biting jaws, their clearly marked thorax with three pairs of jointed legs, not to speak of their subsequent development, all testify to the fact that the animal bélongs to the order of insects. It may cause some surprise that so obscure little creature as the caddis worm (case worm) should be honoured with a popular name, which indiçâtes that the lay mind has long ago become cognisant of it. This is due to a matter of practical utility, for the caddis worms are know to be excellent bait for fishing, and in some localities the name « cad bait » is actually in use. Even superficial investigation will soon show to the collector of caddis worms that there is not one species of these insects building its case with one variety of material in one kind of environment and of another in other surroundings, but that the caddis-worms themselves are different forming genera and species, each with their characteristic to glue together fine grains of sand or very small stones, while the family to the Phryganeidae use piece of leaves and stems for the construction of their case.

The caddis worm, in flowing water, are more easily seen, If we settle down on the bank of a canal or sluggish stream, and Watch the ripples stir the grass roots, and whirl Dead leaves and other debris in a slow dance from stone to stone, our attention may be arrested by small bits of stick, cither resisting the force of the water or movung at an angle to the direction of its flow. We secure a few of the small, apparently inanimate objects that seem to defy Newton’s laws of motion. The discovery will at once be made that the pieces of stick or roots, as well a small particles of mud or stonc, are held together in tubular form, and that the tube itself is inhabited. The owner soon appears at the wider opening of the case, presenting several legs and a dark coloured head. Even more of the body may presently be revealed especially if we place the animal in some water in the hollow of our hand. It will then be seen that behind the dark head is a segmented almost worm-like body, soft and weak, and covered with thick soft threads. There are three pairs of strong legs dispkaying the structure typical insects. More than this the creature does not vouchsafe to display and as we firmily but gently take hold of the front of the animal and try to remove it from its case, it becomes quite obvious that it is attached to the case in some manner, and that our purpose cannot be fulfilled without inflicting grievous bodily harm. This is a typical caddis worm. However great may be the variety these insects display in the mode of constructing the case, in the locality in which they drive, and even in personal appearance, their general manner of living is the same. They are obviously not worms in the scientific sense of the word; their well-developed head with strong biting jaws, their clearly marked thorax with three pairs of jointed legs, not to speak of their subsequent development, all testify to the fact that the animal bélongs to the order of insects. It may cause some surprise that so obscure little creature as the caddis worm (case worm) should be honoured with a popular name, which indiçâtes that the lay mind has long ago become cognisant of it. This is due to a matter of practical utility, for the caddis worms are know to be excellent bait for fishing, and in some localities the name « cad bait » is actually in use. Even superficial investigation will soon show to the collector of caddis worms that there is not one species of these insects building its case with one variety of material in one kind of environment and of another in other surroundings, but that the caddis-worms themselves are different forming genera and species, each with their characteristic to glue together fine grains of sand or very small stones, while the family to the Phryganeidae use piece of leaves and stems for the construction of their case.

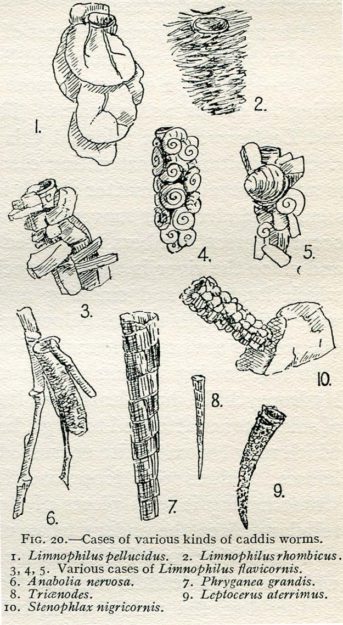

In ponds and still water we frequently find caddis worms whose cases are made of pieces of fine roots or stems. These piece are attached at their middle, and are arranged spirally ; so that the case is very bristly. Very rarely any other material is used. This caddis worm belong to the species Limnophilus rhombicus. Another member of the same genus, Limnophilus flavicornis, uses the greatest variety of material. Stems and sticks are cut into short lengths ; pieces of leaves, specially dead leaves of overhanging tress, and numerous small shells of molluscs, and little stones may all be found in the houses of these creatures. Without ceremony, Limniphilus attaches live pond snails, as well as empty shells to its case, and as the latter is sometimes entirely composed of such shells many will must give way to the intentions of the dominant caddis worm, when a spécial route for a morning ramble is to be selected. As a matter of fact, the small owners of the shells come to an untimely end. The cases of Limnophilus occasionally show uncommon ornamentations-e.g., becch nut, blackened by long exposure in the depths of the pond, with its insufficient supply of oxygen ; fruits and seeds of water plants, such as that of the burr reed ; and wing cases of bettles that have Fallen in the struggle for life.

The case of one of the Phryganeidae-viz., Phryganea grandis- shows extraordinary constructive skill. It is composed of small pieces of leaves, uniform in size, which are attached so as to lie flat in a spiral row of many turns. It is one of the largest case, and at first sight appears to be simply a piece of hollow reed, especially if the leaves become blackened with age. It is cylindrical when inhabited by a mature larva, and narrower at the distant and at a younger stage. A near relative-Triaenodes bicolor- also inhabiting weedy ponds, makes a similar but remarkable slender case.

Althought slightly curved cases of fine sand and mud particles are also built by some pond caddis worms-e.g., Limnophilus vittatus- this type of case is more often found among insects living in canals and streams. Thus the groups Sericostoma and Leptocerus have adopted this mode of building. Other river inhabitants constructing cases of small stones and fragments of vegetable matter attach long twigs and sticks which seem to hinder their movements considerably. These species occur in great numbers in the bed of the river at Cambridge and since the river is the receptacle for all the vesta matches which louging and smoking undergraduate fling into the water, the caddis worms bemow are in Luck’s way, and many a one secures a waxen ornamentation for its house.

In fast-flowing streams species of caddis worms, such as the Hydropsychidae, have learnt the lesson of building fixed abodes of small stones attached to large, heavy, and immovable stones, which may become quite encrusted with colonies of these little houses. Othe spin a loose case of silk round about themselves, strengthening it with pieces of stones and yet others make a tubukar web on the under surface of stones which acts not only as a protective covering but also as e snare for small creatures which serve the caddis worms as food.

How does the caddis worm behave if forcibly deprived of its home ? That depends on the family and on circumstances generally. No general rules as to their conduct can as yet be formulated, but a fex experiments, each repeated several times have had the following results :

Larvae of Phryganea, having been ejected from their cases, have invariably returned to them, and have shown power of identifying their own respective cases when the latter have deliberately been mixed and changed in position.

The same larvae have shown considerable reluctance to construct new cases when their own houses were entirely removed. At first they crept about on the material, consisting of various aquatic plants, sand, stones, pieces of roots, etc.n as if they were searching. They often rested, moving their abdominal segments up and down and finally in the course of from six to ten hours, they had constructed lose, rough covering, and only one out of the four larvae ever built a case again that was typical of its kind.

Some caddis worms, such as Stenophylax and others, whose cases are made of small stones, and who inhabit running water, rarely return to their own or any other case, rarely construct a new case, but perish without making any attemp, even though otherwise normal conditions are maintained by keeping them in running water.

Among the hardiest caddis worms are certainly those of the Limnophilus class. If turned out of their house they cither readily return to it or, if it is not available, they at once start the construction of another case, and are housed once more within the space of half an hour or one hour, though the case may be simply a makeshift, and be modified or replaced by a more durable structure.

A few experiments also go to show that the caddis worms above referred to, with the exception of Limnophilus, will none of them construct cases with material unknow to them. Thus fragments of silk, cotton, paper, fragments of glass, beads, are all of them spurned. It is different with Limnophilus; not only wil larvae of this genus take foreign particles of this description and attach theim to their ordinary cases, but if larvae, deprived of their case and of all natural material, are supplied with such heterogeneous fragments they will readily construct a covering for themselves with them, and will retain they gay decorations for several days even if returned to their more natural haunts in the aquarium. It was interesting to notice that these larvae, on being supplied with fragments of leaves and flower petals, all approximately the same size ans shape and the same in numbers, showed distinct preference for green fragments ; yellow was also largely represented; very little red was selected and no ble. No importance can, of course ; be attached to the experiment, as the various petals also differed in smell and taste, so that choice may not have depended on coulour only.

It is obvious that the construction of the case itself is a direct adaptation to the general conditions under which the caddis worms live, and that the method of construction shows further adjustement on the part of different species of caddis worms to the particular environment in which they find themselves. Any caddis worm would fall an esay prey to the hungry hunters of pool and stream, and thus a covering so umpalatable, of such hard end even hurtful material, shows direct reaction to the stimulus of danger. The fact that many caddis worms build fixed abodes in the bed of streams is of obvious advantage when hurryng ripples interfere with the personal liberty of weak water babies. By chooosing fragments of stone and sans, even through roots may be obtained from the banks and leaves from a many a plant growing in the stream, the caddis worm shows instinctive adaptation, for comparatively smotth cases offer lees resistance to the flow of the water, and homes of stone are lees easily carried away.

Among the caddis worms of the pond similar advantageous adaptations may be noticed. Thus the construction of a case of stems, fibres, and leaves not only means that material for it is always plentiful but that the appearance of such a case is protective in as much as it cannot easily be seen in the tangled mass of vegetation. Some caddis worms, especially of the genera Phryganea and Limnophilus, which make their houses of frgaments of various kinds of materials, suddenly break the uniformity of building by attaching some larger and apparently clumsy object to their case. This seems to be an extraordinary power of adjusting the relative gravity of the larva to the presure of the water. The body of the larva is slightly heavier than water, bulk for bulk, yet when its respiratory filament are filled with air it is buyoed up to such an extent that it has great difficulty to keep at the lower depths of the pond. By means of sinkers-e.g., beech nuts, stones, shells, etc.- the larva so adjusts its weight to the pressure of the water that it can move with maximum facility although it appears to be dragging a heavy load.

The mode of building the case must now be determined, It has been shown that the animal shows considerable selective power as regards the material for building. Much of it can simply be picked up, but stems and leaves have to be cut. It does this by means of its hard mandibles, which are lateral in their movement. They also enable it to lift and move small piece of stone. By means of its front lehs and its mandibles it arranges a few fragments of material, and binds them together with a silken thread, which issues from a gland on the under side of its head, much as in the case of caterpillars. More frgments are added, the animal moving its head to and fro between them till a row of such fragments is strung like a belt round the thorax of the creature. It then adds more particles to the front edge of the belt, pushing it back as it increases in width. In this way a tubular structure is produced, rough with various materails on the outside, according to the specific mode of building of the particular larva, and invariably smooth and silken on the inside, so that no friction is produced when the animal moves. It may cause some surprise that the caddis worm is able to lift comparatively heavy loads, but this insect is strongly built, all the parts required for the building process being supplied with strong muscles attached to a chitinous exoskeleton. Also it must not be forgotten that the animal has not so heavy a burden to carry as the same materials would mean to a créature living on land, since the upward thrust of the water reduces the weight. A problem for which it is difficult to find a solution is presented by the fact that some caddis worms display a High degree of accuracy in the cutting of stems and leaves. This may be seen in Limnopilus rhombicus and Phryganea grandis. The stems and pieces of leaves are as nearly as possible of the salme length or of the same size. The creature must be able to estimate such lengths and sizes. The ready reply will come to hand they know by instinct the kinf of piece required, but the further complication must be noted which several experiments have demonstrated, that the same species, that the same species of larva-e.g., Limnophilus rhombicus-will cut long pieces of root or stem in a large pond and short lengths in a tank; also that if caddis worms with large cases are placed in small tanks the same cases are reduced in size, the insect biting off parts of the house. In confronting problems of this kind, and offering the word « instinct » asa solution, the meaning of the latter must become elastic.

In describing the building of the case mention has been made of the forcible expulsion of the larva frim its house. This many be done in a perfectly painless manner; if a blunt and soft bristle or the head of a pin is gently inserted in the small rear opening of the case, and carefully pushed forward, the inmate will hurriedly escape at the front opening. Of their own accord caddis worms rarely leave their case; only when the water becomes stale and putrid the larvae come out into the open. In collecting specimens from ponds and streams it haas been found that they can be kept out of water among damp weeds for several days, but crowding the larvae in ajr with insufficient supply of water means that they desert their homes and soon perish.

I have once seen a larva of Limnophilus leave its case, shed its skin, and presently construct a new case. I doubt that this mode of procedure is general among the caddis worms. Very little seems to be know of the manner in which these larvae undergo their successives moults.